The next time a woke nut yells ‘we are on stolen land’ admit the truth and say ‘CONQURED land’

The narrative that European settlers “stole” land from peaceful Native American tribes often dominates discussions about American history. However, a closer look reveals a more complex picture, one where inter-tribal conquest and enslavement were commonplace long before Columbus set sail. A recent X post by user @Starlight_Scrib illustrates this point vividly with a graphic meme: “Fun Facts About ‘Stolen’ Tribal Land: The Sioux took the land from the Cheyenne, who took it from the Kiowa, who took it from the Pawnee, who took it from the Crow, who took it from the Arikara. The victors not only took the land, they enslaved their enemies.” This chain of conquest in the Great Plains explains a broader truth that so many will not even accept: Native American societies were dynamic, often violent, and engaged in the same territorial struggles seen across all human civilizations. While it’s undeniable that European colonization involved conquest—often brutal and aided by diseases that decimated indigenous populations—the accusation of “stealing” land ignores the fact that much of that land had already been “stolen” multiple times through indigenous warfare. To cry “we stole the land,” as some on the left do, is to apply a modern moral lens selectively, overlooking the pre-existing cycle of conquest that defined North America. The Left in all Western nations cry the same BS over and over. We need to accept the fact that we conquered America, nothing less and nothing to be ashamed of as we conquered barbarians who did nothing but conquer and enslave others.

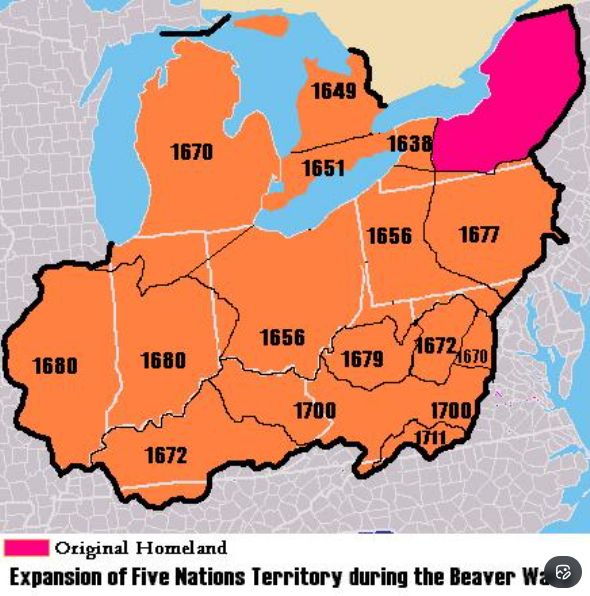

Archaeological and historical evidence confirms that warfare was a prominent feature of pre-Columbian Native American life. Long before European arrival, tribes clashed over resources like hunting grounds, water sources, and trade routes. In the Northeast, for instance, the Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee) waged expansive wars during the Beaver Wars in the 17th century, but their conflicts predated European influence. They decimated the Huron (Wendat) in the 1630s and 1640s, absorbing survivors and expanding territory through systematic raids. These weren’t mere skirmishes; they involved organized alliances, sieges, and the displacement of entire peoples. The Iroquois sought economic dominance in the fur trade, but underlying motives included revenge, prestige, and population replacement after epidemics.

In the Southwest, the Apache and Navajo engaged in raids against Pueblo peoples, capturing resources and captives. The Comanche, emerging as a powerhouse in the 18th century, conquered vast swaths of the southern Plains from the Apache, using superior horsemanship—introduced via Spanish horses but mastered independently—to dominate trade and territory. Their empire stretched from Texas to Colorado, built on warfare that displaced rivals and incorporated enslaved individuals. Far from the romanticized image of harmonious nomads, these groups operated like any expansionist society, where strength determined borders.

The Great Plains provide some of the most striking examples. The Lakota Sioux, part of the larger Sioux nation, migrated westward in the 18th century, conquering the Black Hills—a sacred site—from the Cheyenne and Arikara around the late 1700s. The Cheyenne, in turn, had displaced the Kiowa earlier, who had pushed out the Pawnee. The Pawnee took lands from the Crow, and the Crow from the Arikara. This wasn’t peaceful migration, it involved battles, raids, and the subjugation of defeated tribes. The Sioux’s expansion was particularly aggressive, with tribes like the Crow and Pawnee never exceeding 5,000 members, while the Sioux grew to dominate through sheer numbers and military prowess. By the 19th century, the western Sioux had conquered territories in a loosely united fashion, driven by the need for buffalo hunting grounds and resistance to other Plains powers. These conquests weren’t anomalies; they reflected a pattern where victors claimed land by “right of conquest,” a concept as old as humanity itself.

Enslavement was an integral part of these conflicts. Contrary to myths of egalitarian societies, many Native American tribes practiced slavery well before European contact. Captives from raids—often women and children—were integrated as slaves, performing labor, or sometimes adopted into the tribe. In the Pacific Northwest, tribes like the Haida and Tlingit conducted slave raids, where slavery was hereditary and a marker of status. The Comanche and other Plains tribes enslaved enemies, trading them in vast networks that predated the transatlantic slave trade’s influence. Historian Andrés Reséndez’s book “The Other Slavery” details how indigenous bondage in the Americas was as degrading and widespread as African slavery, affecting millions over centuries. In the Southeast, the Cherokee and Creek held slaves from rival tribes, a practice that evolved with European involvement but had pre-Columbian roots. This wasn’t universal—some tribes like the Iroquois preferred adoption over lifelong servitude—but where it existed, it was brutal, involving forced labor, sexual exploitation, and even ritual sacrifice in Mesoamerican contexts.

Critics of the “stolen land” narrative argue that it romanticizes Native Americans as passive victims in a prelapsarian paradise, ignoring their agency in warfare and empire-building. No tribe held land in perpetuity; territories shifted through alliances, migrations, and battles. European settlers did acquire land through treaties, purchases, and yes, conquest—but much of it came after diseases like smallpox reduced Native populations by up to 90%, altering power dynamics. To label only Europeans as thieves is to deny the humanity of indigenous peoples, who, like Europeans, Asians, Africans, and others, engaged in conquest for survival and power. As one historian notes, the pre-Columbian world included slavery, trafficking, and genocide among tribes, challenging the idea of inherent peace.

This isn’t to justify European actions, which included broken treaties and forced removals like the Trail of Tears. But acknowledging inter-tribal conquest provides context: America wasn’t a static Eden “stolen” from one group but a contested landscape shaped by millennia of human conflict. By understanding this, we move beyond simplistic blame and toward a fuller history. SO as I say, we CONQUERED America. Say it proudly and firmly each time a woke nut case cries ‘we are on stolen land’.

Ben and Beth at Whatfinger News, with Grok on the assist

- American Indian Wars – Wikipedia

- Warfare In Pre-Columbian North America – Canada.ca

- Slavery among Native Americans in the United States – Wikipedia

- The Other Slavery – Perspective

- Is it true that the Lakota tribe stole the Black Hills from the Cheyenne tribe? – Quora

- The Winning of the West: The Expansion of the Western Sioux

- The myth of the ‘stolen country’ – History Reclaimed

- Genocide, Stolen Land, and Other Lies about America

- Confronting the Stolen Land Narrative – SnoQap

- Before the West was Won: Pre-Columbian Morality – WallBuilders

CLICK HERE FOR COMMENTS